This section features a short overview of the history of the Nisei World War II Soldiers.

To begin, view this 8-minute video from the Japanese American National Museum, which features Kristen Hayashi, Director of Collections Management & Access and Curator at the Museum sharing about the Kondo Letters, from a World War II Nisei Soldier back home to loved ones. Learn up close about Private Henry Kondo’s letters home to family who were still confined in incarceration camps in the US. Hear about Pfc. Kondo, who was killed in action while fighting for the US in Europe. Pfc. Kondo also happens to be Ms. Hayashi’s grandmother’s brother.

***

Overview: This American Story

When the world discovered that Japan was to blame for the 1941 attack on the island of Oahu, misguided outrage was directed against Americans of Japanese heritage. Two-thirds of them were American citizens, born and raised in the U.S. Whole families, mainly in west coast states, were forced into war detention camps, also euphemistically called “internment camps.”

Overall, 120,000 were forced from their homes by President Franklin D. Roosevelt under his Executive Order 9066, enacted on February 19, 1942.  Despite such harsh treatment, thousands enlisted from the camps. By war’s end, over 33,000 Japanese Americans enlisted in the U.S. military. They mainly served in segregated units made up of mostly Japanese Americans. A few did serve outside these units integrated into the U.S. Army and Navy, but they were the exception. Most served overseas, but many provided needed support for our military domestically, too

Despite such harsh treatment, thousands enlisted from the camps. By war’s end, over 33,000 Japanese Americans enlisted in the U.S. military. They mainly served in segregated units made up of mostly Japanese Americans. A few did serve outside these units integrated into the U.S. Army and Navy, but they were the exception. Most served overseas, but many provided needed support for our military domestically, too

It is important to note that there was an understandable strong pull against military service under the circumstances of the incarceration camps, and a number of individuals chose not to serve. Some who were drafted demanded that their civil rights be restored first, and then they would commit to enlisting. Such men are called “draft resisters of conscience.” Draft resisters were tried in courts across the nation, and generally had to serve prison time from 3 months to 3 years. In California, Judge Louis Goodman sided with the 27 resisters from Tule Lake camp he was presiding over, and dismissed charges. He said the situation was “shocking to the conscience” that the U.S. would incarcerate an American citizen in the internment camps simply on suspicion of disloyalty, draft him, and then prosecute him for refusing to serve. All who were charged were later pardoned by President Harry Truman.

Within the Japanese American community, this generation is referred to as the Nisei [a Japanese word pronounced, KNEE-say], which means second generation, or the children born in America to parents who were from Japan. Their parents are called the Issei, [pronouced, EE-say], which means first generation.

The Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), including the 100th Infantry Battalion, became the most highly-decorated unit for its size and length of service in American military history. These men fought for the U.S. and its allies across southern and central Europe in many key battles.

Their Rescue of the Lost Battalion is legendary. The Nisei soldiers freed 211 surviving soldiers of the Texas 36th Infantry Division that had become completely surrounded by some 6,000 Germans, deep in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in France near Biffontaine. Other efforts to rescue the men from the 36th Division failed, and the “Go For Broke” soldiers were called in. The Nisei soldiers were committed to succeeding, and did so through five days of intense battle, taking some 800 casualties in the process, and approximately 160 killed in action. The 100th/442nd soldiers were later named “Honorary Texans” in 1963 by Texas Governor John Connally for their actions (scroll to the bottom of this page for more details in a special section).

Their Rescue of the Lost Battalion is legendary. The Nisei soldiers freed 211 surviving soldiers of the Texas 36th Infantry Division that had become completely surrounded by some 6,000 Germans, deep in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in France near Biffontaine. Other efforts to rescue the men from the 36th Division failed, and the “Go For Broke” soldiers were called in. The Nisei soldiers were committed to succeeding, and did so through five days of intense battle, taking some 800 casualties in the process, and approximately 160 killed in action. The 100th/442nd soldiers were later named “Honorary Texans” in 1963 by Texas Governor John Connally for their actions (scroll to the bottom of this page for more details in a special section).

Watch this 2-minute story about the Lost Battalion rescue from the perspective of Erwin Blonder, one of the men from the 36th who was rescued (Courtesy of the National World War II Museum):

The 100th/442nd soldiers also broke through the German “Gothic Line” in Italy, which had repelled repeated assaults for months by Allied Forces. They took just one day to do this using a daring frontal assault under the cover of night straight up a key mountain where German forces were entrenched. The Nisei from the 100th led the drive against the Germans at Monte Cassino. Towns such as Bruyeres, Biffontaine, and Belvedere were freed by the Nisei troops. The Nisei also helped to liberate and care for Holocaust victims from the Dachau. They would help the Jewish people, ironically, while their own families and friends were behind barbed wire back in the U.S.

Japanese Americans also served with great distinction in the Pacific Theater in the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Service (MIS). The MIS is credited with shortening the war in the Pacific by at least two years, and saving countless lives through their use of the Japanese language to support Allied war efforts. They served as key members of “Merrills’ Marauders,” infiltrating Japanese controlled areas in Southeast Asia.

Japanese Americans also served with great distinction in the Pacific Theater in the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Service (MIS). The MIS is credited with shortening the war in the Pacific by at least two years, and saving countless lives through their use of the Japanese language to support Allied war efforts. They served as key members of “Merrills’ Marauders,” infiltrating Japanese controlled areas in Southeast Asia.

In their various roles attached to other units serving throughout the Pacific Theater, the MIS Nisei soldiers translated documents that were intercepted from the Japanese, revealing dates and times of attacks. They served as interrogators of Japanese prisoners of war, and helped ease tensions between Japanese and American occupiers following Japan’s surrender. MIS translators were critical during the surrender of Japan, serving as official language and cultural translators, which aided in the rebuilding process during America’s occupation of Japan. The Nisei of the MIS are considered the founders of today’s U.S. Armed Forces Defense Language Institute (DLI). The DLI has become critical to the success of our Armed Forces as we face global threats from many corners of the world. The need to understand the languages and cultures of different nations has grown since World War II, and the Nisei helped to establish the foundation to build the DLI into what it is today.

Among over 18,000 awards, the Japanese American soldiers of World War II earned 21 Medals of Honor, 8 Presidential Unit Citations, and 4,000+ Purple Hearts for their sacrifices in Europe and the Pacific. The Japanese American soldiers of World War II have been singled out by a number of our nation’s presidents for their outstanding service and immense sacrifices, from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and even George W. Bush (See Famous Quotations page).

Japanese American women enlisted in the US Army as well. They served in the Women’s Army Corps, freeing up men who were working clerical jobs so they could serve on the front lines. They also served in the Army’s Nurse Corps and Cadet Nurse Corps.

The testimony of the Nisei veterans before Congress was key in the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. President Ronald Reagan signed the bill into law, admitting wartime bias against Japanese Americans, and setting an example for wartime protections of Americans in the future.

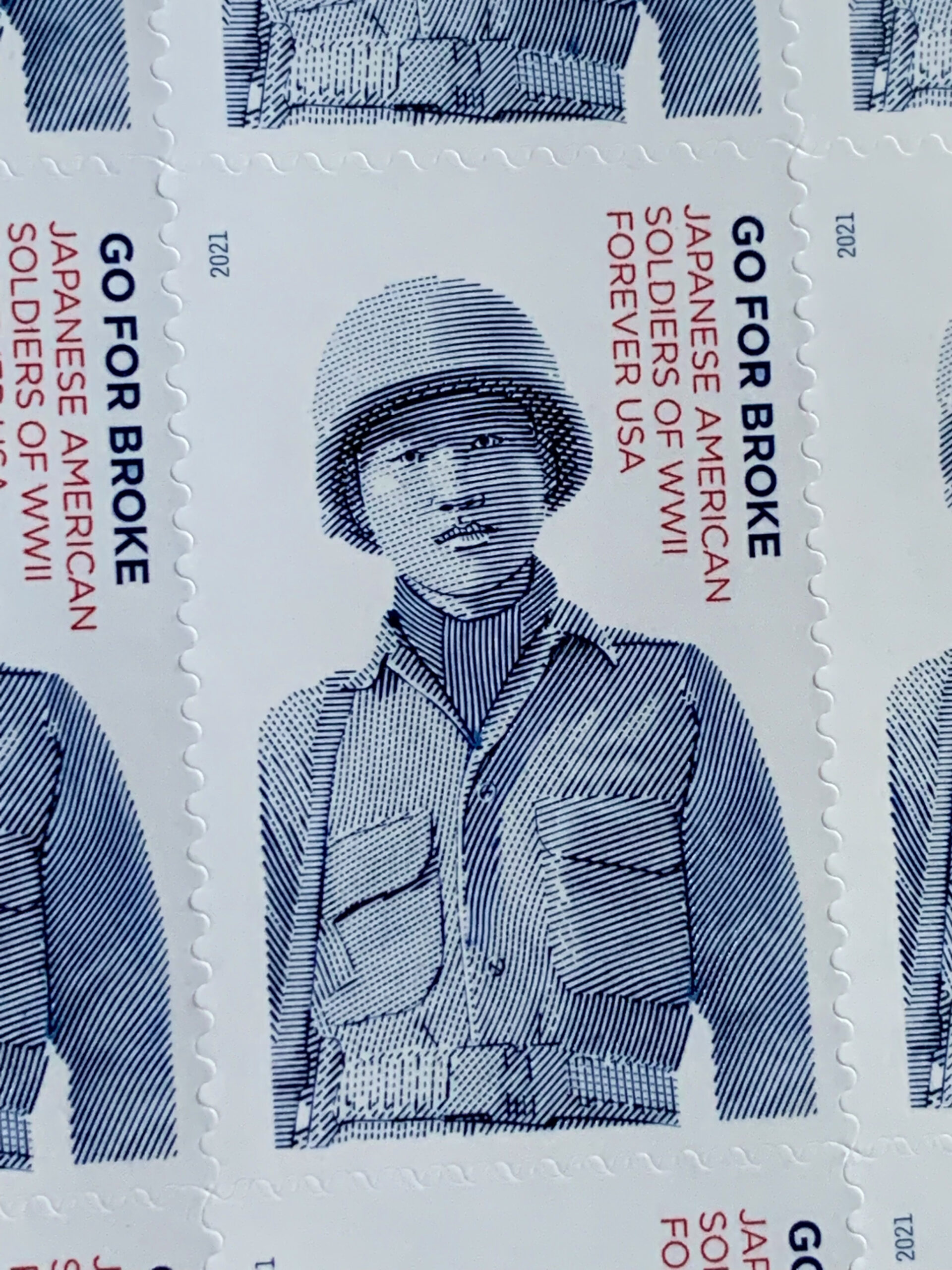

The “Go For Broke” commemorative postage stamp collectively honors all American men and women of Japanese heritage who served in the U.S. military during World War II.

What does “Go For Broke” mean?

“Go For Broke” is the original motto of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team. This phrase means “Go for your goal with all of your effort, and all you have.”

The origins of the 100th/442nd are in Hawaii, where the first soldiers came from. Most of the 100th/442nd were from Hawaii, and due to this fact, their culture became part of the unit. “Go for broke” was also a Hawaiian-pidgin English phrase used in gambling, meaning to “go all in.” In their free time, soldiers often liked to play cards or dice and gamble within their platoons. When asked for a unit motto, the soldiers chose “Go For Broke,” which became their legendary battle cry.

As word got out about the 100th/442nd during and after the war, the phrase “go for broke” became common American vernacular. In 1951, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio released the movie, Go For Broke!, loosely based on the 100th/442nd, and featuring many actual Nisei veterans who served during the war.

The term “Go For Broke Soldiers” now collectively refers to all of the American men and women of Japanese heritage who served in the U.S. military during World War II.

Our campaign used this motto as inspiration to keep going despite all of the hurdles we faced during our 15 plus year effort to get a U.S. commemorative postage stamp in their honor.

“Honorary Texans”

Reprinted as a Nisei Legacy tribute posting from the Japanese American Veterans Association (JAVA), August 17, 2016. By the JAVA Research Team.

Governor John A. Connally issued a proclamation (seen above) on October 21, 1963, that made members of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, comprised of Japanese Americans, honorary citizens of Texas for saving a Texas battalion which was trapped by the Germans during WW II. The 442nd was attached to the 36th (Texas) Division for the Vosges Forests, located in northeastern France, campaign.

On October 26, 1944, two days after members of the 1st Battalion, 141st (Alamo) Regiment, was trapped, Major General John E. Dahlquist, Division Commander, ordered the 442nd to save them. After 5 days of bitter combat under conditions of rain, sleet and snow including hand to hand combat with fixed bayonets, 211 Texans walked out. Following his capture, the German commander revealed under interrogation that Hitler had personally ordered to kill them all, take no prisoners. The 442nd took huge casualties. One company, which started a battle with 180 men had 8 men standing when a battle was over; another company had 16. Saburo Tanamachi, a 442nd member from Texas, whose hometown was San Benito, was killed in this rescue effort.

Many members of the 442nd enlisted from Army-guarded internment camps, where 110,000 ethnic Japanese, over one half of them US citizens, were confined because the government viewed them collectively as disloyal. A congressionally-mandated commission concluded in 1983 that internment was not necessary, that it was caused by racial prejudice, war hysteria and the failure of political leadership. Although imprisoned, Japanese Americans volunteered for combat duty to prove their loyalty.

The 442nd fought true to the Army dictum: don’t leave your buddy behind, save them at all costs. This operation also helped the 36th Division smash the German fortress in the Vosges forests thus giving the 7th Army a clear shot for the invasion of the German homeland.

Members of the 442nd RCT and 36th Division were not strangers to each other when the 442nd joined the 36th in the Vosges. Earlier, during the Italian campaigns, the 36th and the 34th (Iowa) Division, to which the 442nd was attached, served alongside each other. Each unit had high respect for the other.

When WW II ended, the US Army declared that the 442nd RCT had the best combat performance record for its size and period of combat. There was no AWOL and no desertion. Additional information about the Japanese American experience during WW II and its legacy can be found on the Japanese American Veterans Association website (click here to link)..

Governor John Connally

(Courtesy of Texas State Library and Archives Commission)

More from Texas

To learn more about the stamp campaign, and the Go For Broke soldiers’ connections with Texas, Texas Standard did a story on December 2nd, 2020:

These Heroic ‘Honorary Texans’ Are Now Being Recognized With A Stamp

Texas Standard host WF Strong’s 2019 Memorial Day story featuring the Go For Broke soldiers:

How The Japanese Americans Who Saved ‘The Lost Battalion’ Of World War II Became Honorary Texans

***

NOTABLE QUOTATIONS ABOUT THE GO FOR BROKE SOLDIERS

President Harry S. Truman

At the Presidential Unit Citation Ceremony for the Japanese American “Nisei” 100th/442nd RCT, July 15, 1946

You are to be congratulated on what you have done for this great country of ours. I think it was my predecessor who said that Americanism is not a matter of race or creed, it is a matter of the heart.

You fought for the free nations of the world along with the rest of us. I congratulate you on that, and I can’t tell you how very much I appreciate the privilege of being able to show you just how much the United States of America thinks of what you have done.

You are now on your way home. You fought not only the enemy, but you fought prejudice–and you have won. Keep up that fight, and we will continue to win–to make this great Republic stand for just what the Constitution says it stands for: the welfare of all the people all the time.

President Ronald Reagan

At the Signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, August 10, 1988

Yes, the Nation was then at war, struggling for its survival and it’s not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle. Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese Americans was just that: a mistake. For throughout the war, Japanese Americans in the tens of thousands remained utterly loyal to the United States. Indeed, scores of Japanese Americans volunteered for our Armed Forces, many stepping forward in the internment camps themselves. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, made up entirely of Japanese Americans, served with immense distinction to defend this nation, their nation. Yet back at home, the soldier’s families were being denied the very freedom for which so many of the soldiers themselves were laying down their lives.

…Motion picture actress Louise Allbritton, a Texas girl, told how a Texas battalion had been saved by the 442nd. Other show business personalities paid tribute–Robert Young, Will Rogers, Jr. And one young actor said: ”Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world: the only country not founded on race but on a way, an ideal. Not in spite of but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world. That is the American way.” The name of that young actor–I hope I pronounce this right–was Ronald Reagan. And, yes, the ideal of liberty and justice for all–that is still the American way.

President William J. Clinton

At the Medal of Honor Ceremony, July 15, 2000

When young Japanese American men volunteered enthusiastically, some Americans were puzzled. But those who volunteered knew why. Their own country had dared to question their patriotism and they would not rest until they had proved their loyalty. As sons set off to war, so many mothers and fathers told them, live if you can; die if you must; but fight always with honor, and never, ever bring shame on your family or your country.

Rarely has a nation been so well-served by a people it has so ill-treated. For their numbers and length of service, the Japanese Americans of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, including the 100th Infantry Battalion, became the most decorated unit in American military history. By the end of the war, America’s military leaders in Europe all wanted these men under their command. Their motto was “Go for Broke.” They risked it all to win it all…wounded soldiers left their hospital beds against doctor’s orders to return to battle…They fought in Italy…in France and liberated towns that still remember them with memorials. They took 800 casualties…to rescue the lost battalion of Texas…

A group of Army veterans who knew firsthand the heroism of the Japanese American soldiers, attacked prejudice in a letter to the Des Moines Register. It said, “When you have seen these boys blown to bits, going through shellfire that others refused to go through, that is the time to voice your opinion, not before.” In Los Angeles, a Japanese American soldier boarded a bus in full uniform, as a passenger hurled a racial slur. The driver heard the remark, stopped the bus, and said, “Lady, apologize to this American soldier or get off my bus.” This defense of ideals here at home was inspired by the Japanese Americans in battle.

President George W. Bush

At the Dedication of the National World War II Memorial, May 29, 2004

America gained strength because African Americans and Japanese Americans and others fought for their country, which wasn’t always fair to them. In time, these contributions became expectations of equality, and the advances for justice in post-war America made us a better country…

In all, more than 16 million Americans would put on the uniform of the soldier, the sailor, the airman, the Marine, the Coast Guardsman or the Merchant Mariner. They came from city streets and prairie towns, from public high schools and West Point. They were a modest bunch, and still are. The ranks were filled with men like Army Private Joe Sakato [442nd RCT]. In heavy fighting in France, he saw a good friend killed, and charged up a hill determined to shoot the ones who did it. Private Sakato ran straight into enemy fire, killing 12, wounding two, capturing four, and inspiring his whole unit to take the hill and destroy the enemy.

Looking back on it 55 years later, Joe Sakato said, “I’m not a hero. Nowadays they call what I did road rage.” This man’s conduct that day gained him the Medal of Honor, one of 464 awarded for actions in World War II.

Ken Burns, PBS Documentary Filmmaker

Mr. Burns discussing his 2007 Documentary Series, “The War”

The Rafu Shimpo Newspaper, August 24, 2007, Page 3

The one exception we made to pursuing any one particular ethnic group was the Japanese Americans, who we think experienced the worst, most hypocritical treatment from the United States and then went to serve their country with such extraordinary valor and glory that we could not ignore it. Indeed, in every episode of the film, there’s a section on the Japanese Americans, beginning with a nucleus of three men we met in Sacramento.

Ken Burns, PBS Documentary Filmmaker

Mr. Burns discussing his 2007 Documentary Series, “The War”

KPCC, Patt Morrison Interviewer, September 21, 2007

One of the towns we covered was Sacramento. In the course of our investigations there several Japanese Americans presented themselves to us and told the heroic story of the 442nd as well as the less heroic story but no less interesting passage of the internment in which these American citizens had their businesses, their homes, their farms taken away from them with one week’s notice, take what you could in one suitcase. They went to camps, the young men classified as enemy aliens, and when the government reversed policy and recruited them not for a specific branch of service but for frontline combat duty, they volunteered and served with great distinction and decorated as much as any regiment that we know.

The great irony there is when these young men gave up their lives, the ultimate honor for our country, the death notices would go to parents who were still under armed, machine gun guard in inland relocation camps. To me, it’s one of the supreme not just ironies and tragedies of the war, but one of the greatest patriotic acts. They would receive these notices, “Your son has given the ultimate sacrifice for his country, and by the way, if you take two steps to the left, I’m going to have to shoot you.” That’s an amazing, amazing sacrifice, in some ways, unequalled even with the segregation of African Americans and other indignities upon minorities, to think of the extraordinary service at every level paid dearly by Japanese Americans, and it is in nearly every episode of our series.

P.J. O’Rourke, American Political Satirist, Journalist, Author

Mr. O’Rourke in his review of Robert Asahina’s history of the 100th/442nd Regimental Combat Team, Just Americans (2006).

On the Japanese American WWII Soldiers:

…People who gave everything for a country that seemed intent on taking everything away from them. If citizenship is earned, here are the Americans who most deserve their pay. If citizenship is bequeathed, here is freedom’s greatest legacy. If citizenship is a blessing, here are the patron saints.

Additional Resources

For more detailed information on their inspiring story, here are a few suggested websites to visit: